Volume 2

Information, ideas, questions and answers about accessibility as a core design principle for communities

Welcome to A Building for Your Community, a free resource series by New Practice. We are an architecture practice who have been fortunate to be involved in lots of exciting projects, working in collaboration with communities to explore future plans for their buildings.

You might already be managing a community building, or perhaps you are a member of an organisation looking to embark upon finding one. Or perhaps you are just curious about what community-led development entails.

What do we mean when we talk about accessibility?

Accessibility isn’t all about lifts and ramps.

Accessibility can be viewed as ways of making things: perceivable, understandable, operable, and robust. Access in the built environment is relevant for everyone and everybody and inclusive spaces are better for everyone.

Place-based practice is a collective process to achieve outcomes that may be impossible without new thinking and collaborative action. When we talk about creating accessible spaces, we are talking about what it takes for people to feel empowered and independent within these spaces to exist, feel comfortable and engage without experiencing significant barriers.

Accessibility:

the quality of being able to be reached or entered

the quality of being easy to obtain or use

the quality of being easily understood or appreciated

-

Under the Equality Act 2010 disability is defined in relation to the duration and impact of impairment or symptoms rather than any specific diagnoses. The reason this matters is that enforcing disability rights in the UK is largely only available to people who are or have been legally-disabled.

The legal definition of disability focuses on the untreated or undiagnosed state of the condition or impairment. Many people who don’t consider themselves disabled could be legally-disabled for Equality Act purposes. Some people who identify as disabled may find themselves not accepted as legally disabled in some situations.

There are a handful of conditions: HIV, Cancers, Multiple Sclerosis (MS) and registered Partial or full Sight Impairments that are automatically considered legal disabilities from the point of diagnosis in the UK. This is because organisations representing these impairment-groups successfully lobbied for their automatic definition in the past.

“Why, then, does the idea of disability being creative and avant-garde seem so absurd? Is it because of taken-for-granted assumptions about disabled people: that they are in need of the help of others, are passive consumers of services, constitute a minority of individuals in society who (unfortunately) must bear the brunt of their own medical problems? Is it because creativity slips sideways into ‘art therapy’ when undertaken by disabled people, and into functional and clinical solutions when undertaken by architects?

What if, instead, we see that re-thinking disability enables us to explore critically and creatively assumptions about, and relationships between, disability and ability which, in turn, can offer better ways of understanding the architectural implication of both bodily diversity and everyday socio-spatial practices?”

- Jos Boys, Doing Disability Differently

People with disabilities and support needs are constantly required to create and recreate their access to spaces in a world not designed for them.

“Accessibility is not about compensating impairments that hinder ‘normal’ building occupation, rather built space can enable encounters of architectural and experiential significance, whatever a person’s unique physical relationship to the world”

- J. Kent Fitzsimmons, Disability, Space, Architecture: A Reader

What is inclusive design?

Impactful inclusive design takes a people-centred approach, considering a range of abilities and disabilities, all age groups and backgrounds. It seeks solutions that reflect the different faiths, and meet the specific or general needs of all users, regardless of ability, health, gender identity, or neurocognitive profile. People should be able to make effective, independent choices about how they use places and spaces without experiencing undue effort or separation and be able to participate equally in the activities the area offers.

No matter how physically accessible a space is, without clear operational policy mechanisms, the accessibility of the service and user experience is likely to be compromised. Therefore, sufficiently robust provision, criterion and practices must be established by building management and end user operators and should include the development of active management plans to ensure that accessibility does not diminish over time.

In broaching this topic we are joined by Buro Happold to explore their work in this field.

The DisOrdinary Project at The Tate Modern

True inclusive design benefits all of us, throughout our lives.

It aims to remove barriers from the environment that impact not only disabled people, but families with young children, people carrying heavy baggage, during pregnancy, ill health, recovering from surgery, and as our lives change through age or circumstances.

The five principles of inclusive design are listed below and it is these principles that should be adopted through projects:

Places people at the heart of the design process

Acknowledges human diversity and difference

Offers dignity, autonomy, choice and spontaneity

Provides for flexibility in use

Provides buildings and environments convenient, safe and enjoyable for everyone to use.

Inclusive design is the essence of good design but it goes beyond ‘accessibility’ and incorporates a broad range of design considerations.

Over the last few years, a profession that was founded upon accessibility for disabled people has expanded to many other equality strands as they relate to the built environment - by addressing these topics, we can shape a more inclusive outcome where everyone has the opportunity to enjoy and flourish in the built environment.

The following list represents many of the areas that are now encompassed in inclusive design assessments:

Sanitary accommodation: (wheelchair and ambulant accessible, gendered and gender neutral, family, and children’s toilets, Changing Places Toilets, wudu and lactation/parent with child facilities.

Neurodiversity

Menstrual and Menopausal health

Cultural and faith considerations

Mental health and wellbeing in buildings

Biophilic design

Inclusive play

Women’s safety

Buro Happold sponsored the new guidance PAS 6463: Design for the mind – Neurodiversity and the built environment with technical authorship and contributions from specialist disciplines. The guidance applies to mainstream buildings and external spaces for public and commercial use, as well as residential accommodation for independent or supported living.

During our research it was found that a significant number of people find aspects of the built environment difficult or uncomfortable to use. There are many people who have hypersensitivity or are prone to ‘sensory overload’. For example, many people with neurodivergence or neurodegenerative conditions. These people may be overwhelmed due to features in the built environment. Therefore, it became apparent that alongside designing places to accommodate our diversity in form, size and physical ability, there is also a profound need to design for neurological difference.

The Design for the Mind PAS guidance provides a great opportunity to enable professionals working on projects in the built environment to carefully consider neurodiversity in the design.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that an inclusive project/space does not attempt to meet every need of every person, but by considering the diversity of society it can break down barriers and exclusion and can often lead to a more effective and sustainable outcome. By designing all environments for as broad a demographic as possible, buildings can become more flexible and able to adapt to change without the need for costly and time consuming adaptations. The overall aim being to design spaces and places that are comfortable for everyone to use, visit and enjoy.

- by Buro Happold

How to begin?

Beginning a project with accessibility as a core outcome means asking the right questions from the beginning.

Answering these questions can help to make decisions, direct budget and balance different needs to achieve a reasonable compromise for everyone.

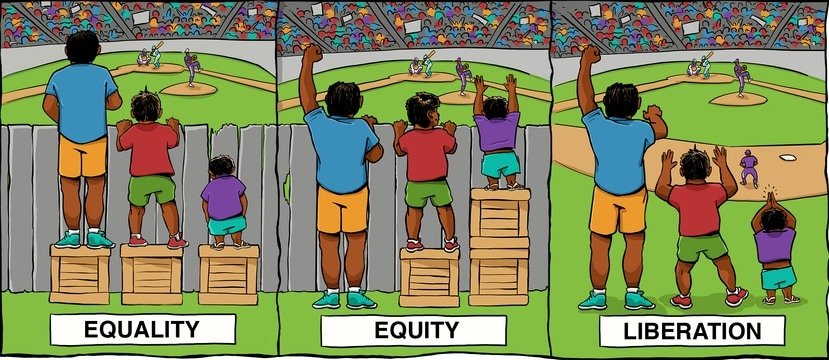

Diversity is a fact

Equity is a choice

Inclusion is an action

Belonging is an outcome

… some questions to get you started

Who might use the space?

Physical Accessibility and Reasonable Adjustments

Whilst access is not simply ramps and lifts, the physical accessibility of a space can, and should be considered carefully. This will mean including physical solutions such as: hearing loops, braille signage, ramps, passenger lifts, compliant handrails and door handles. The starting point is to ask: “who might use this space?” and to think broadly about the range of requirements they might have.

How will people feel welcomed?

Getting Around and Accessibility of Language

For this, we should consider how people arrive at a building, or their most likely routes through a space. Is it clear and obvious where they should go? Will they feel able and comfortable to walk through this door?

Often in buildings we rely on signs to tell people this information. The average reading age of the UK is 9 years old, and within communities there can be significant and generational literacy issues, including those with English as a second language, or those with learning difficulties and disabilities. This changes the way we think about signs and wayfinding within buildings and outdoor spaces. Can all signs be written in plain language? Could we use visual wayfinding (trails, icons and colour) to support written language? Do we need signs at all?

Tools such as these, even though they are primarily designed for online content, can help support you and your design teams to understand legibility.

What is the sensory experience of this space?

Different needs have different solutions

Different communities will require different types of accommodation, or adjustments. Physical needs are perhaps simpler to address as there are clear solutions to clear challenges.

Some people have needs that might not seem obvious at first and may conflict with each other. Will the space be noisy or overwhelming? Is there some quiet place to go to? Will the space have strong smells or bright lights? Is there a room nearby with a controllable sensory experience?

We can’t ever know everyone’s needs or everyone’s access requirements, the key here is to ask the right questions and listen to the answers.

Talking About Access

To discuss the theme of accessibility in architecture and urbanism, New Practice conducted a one-to-one interview with Thea McMillan Director & Architect at Edinburgh based practice chambersmcmillan.

Thea brings a reflective perspective from her wealth of experience engaging young people and creating accessible designs; from working first hand with the Disabled Scouts Group in Scotland through to award winning design for The Ramp House - her own family home that is completely accessible by wheelchair.

Everyone’s needs are different

As we’ve already touched on, there are many ways to consider inclusion and accessibility. One size will not fit all and different people will need different accommodations in the design of spaces and places.

For public and community buildings, there will always need to be a compromise found which suits the most people and is budget appropriate. Not everyone will get everything they want, but the aim is to provide most people with everything they need.

Dealing with compromise and conflicting needs

Different people have different access needs.

Some examples of groups who might need different accessibility measures include:

Adults (parents or guardians) of young children

Older and ageing people including those with age related health concerns

Neurdivergent people including those with ADHD, Autism Spectrum conditions, Dyslexia, Dyspraxia, and Tourette’s

People with English as a second language and/or literacy challenges

People with learning disabilities and difficulties

People with long term and chronic health conditions

People with mental health concerns

People with physical disabilities

People with sensory disabilities including blind, visually impaired, hard of hearing, d/Deafblind and d/Deaf communities

Different people have different access needs, someone who needs dim lighting due to sensitivity to bright lights and someone who needs bright lighting due to low vision. How can these two people work in the same space?

Where possible, we should design for both needs equally. For example, some people need simple language and others need precise formal language - you can have two versions. Providing a range of options rather than making somewhere accessible to one group and inaccessible to another. You can also assess the level of need and make adjustments depending on the circumstance.

Can you find a compromise with the least negative impact?

Tactile paving is often an example used to highlight the different access needs of those with mobility impairments and visual impairments. They help those with visual impairments but can hinder the safe movement of those with mobility aids.

As Disability Activist Karrie Higgins recently said, sometimes conflicting needs can even exist within the same person. Accessibility is difficult but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t bother with it.

Being prescriptive about what accessibility is and providing blanket solutions, despite having good intentions, often ignores and erases experiences and access needs.

Full accessibility may not possible but we can work to acknowledge, accept and cater to everyone’s needs as best we can.

This starts with listening to disabled people.

Accessibility for me is a feeling, a feeling of being held in a safe space - both mentally and physically.

A feeling of openness and shelter simultaneously, It lends itself to the sensation of being able to enter and leave, communicate freely and respectfully amongst others of all walks of life and human needs. This paper cut collage piece pictures a small community group being held in giant palms expressing that sensation of safety, open, colourful self expression and relaxed peace of mind in amongst the cosmos chaos.

‘A Feeling of Openess and Shelter’ a visual response by Greer Pester

Where else can I look for information?

Ageing Populations & Design for Dementia

Intersectional Accessibility

Online and Digital Spaces

Existing Buildings/Greenspace and Accessibility

Inclusive Design Resources and Articles

Just Wait

- by Jessica Noël-Smith

Jessica Noël-Smith is an architect and researcher with a specialism in Accessibility, Age and Dementia.

Her passion for accessible architecture was inspired from early work with children with motor impairments (such as Cerebral Palsy) undertaking Conductive Education. Over the course of summers from 2006 to 2011, she worked closely with a remarkable cohort of young summer school attendees and their families at The Lighthouse Trust Summer School in Donaghadee, Northern Ireland. There, Jessica experienced first-hand how the built environment played a vital role in the wellbeing of each of these young individuals’ lives. She witnessed these dynamic and vibrant children coming to realise as they grew older, that they had to live differently to their able-bodied peers due to the inadequacies of the built environment that ultimately disabled them.

No matter how physically accessible a space is, without clear operational policy mechanisms, the accessibility of the service and user experience is likely to be compromised.

Therefore, sufficiently robust provision, criterion and practices must be established by building management and end user operators and should include the development of active management plans to ensure that accessibility does not diminish over time.

The places we live, work, play and visit can make or break our relationship with the world.

If you have ever felt unable to access, use, or take part in any environment, you will understand the feeling being unwelcome, overlooked, undervalued and ultimately ‘dis-abled’ by the physical and social constructs around you (WHO def. of Social Disability, 2023).

If you have yet to experience difficulty in accessing a place or space, just wait.

Over the course of your lifetime you may experience disability yourself - it might be temporary such as a broken limb, a complicated pregnancy, or recovery from surgery. Or it might be the onset of a progressive autoimmune condition (MS), or cognitive decline (dementia), or an age-related impairment such as general frailty, sight or hearing degeneration.

If not directly affected yourself, you might be supporting someone close to you such as your spouse, parent, child, or grandparent. By the time we are of pension age, at least 45% of us will be disabled (ONS / DWP Family Resource Survey, 2023); and of those born since 2015, it is projected that 1 in 3 people will develop dementia in their lifetime (Alzheimer’s Research UK, 2015).

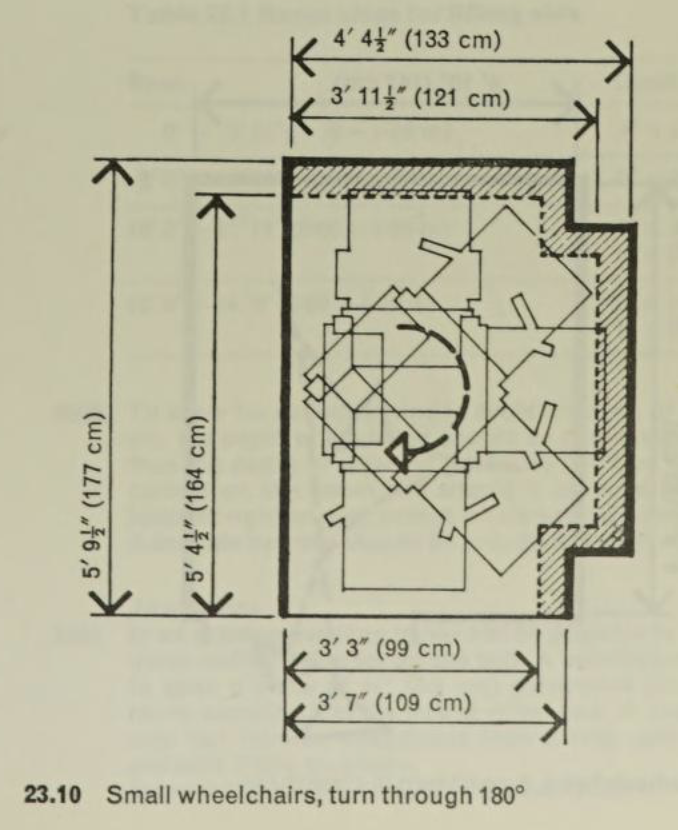

Creating inclusive and accessible environments is everyone’s business. Yet, even with the most innovative advancements in assistive technology, and our progressive understanding of physical and cognitive impairments – we still design spaces today using technical design guidance that was conceived in 1963 when Selwyn Goldsmith published the first technical design guidance for architects, ‘Designing for the Disabled: A Manual of Technical Information’, (Goldsmith, 1963. BS 8300:2018). This was the birth of our ubiquitous ‘1500mm turning circle’ we still apply when planning spaces today.

Consider the advancements society has made since 1963 in the context of human rights: the ‘Social Model of Disability’ was coined by Mike Oliver in 1983; (Oliver, 1990); The Disability Discrimination Act in 1995 and The Equality Act in 2010.

In 1963, the introduction of defined accessible activity spaces for public buildings was revolutionary because most wheelchair users would have been confined to institutions. At the time, Selwyn Goldsmith was at the forefront of the Disability Rights Movement - isn’t it time for the next revolution in accessible design in 2023? Can’t we do better than using a 60-year-old activity space when designing modern environments? How can we move on from the application of minimum design guidance being used as the standard?

Designers of buildings, spaces and places hold the power to enable the many, not the few. Where better to start than with buildings that are at the centre of our communities, to exemplify best practice as the new standard, and to pave the way for a most inclusive society.

Making accessible and inclusive spaces is critical for communities.

Lots of people cannot currently access venues for services, suppport or social gathering.

We hope you can ask the right questions to begin making your buildings,

your public space and your assets more inclusive to build better communities.

Thank you for reading!

This concludes Volume 2 of A Building for Your Community, ‘Making Accessible Places’

Please don’t be strangers, we are open for conversations and to provide support and looking forward to hearing from you.

Get in Touch to talk, we can do that by email or video call.